Search

Items tagged with: mongoDB

Earlier this year, Cendyne wrote a blog post covering the use of HKDF, building partially upon my own blog post about HKDF and the KDF security definition, but moreso inspired by a cryptographic issue they identified in another company’s product (dubbed AnonCo).

At the bottom they teased:

Database cryptography is hard. The above sketch is not complete and does not address several threats! This article is quite long, so I will not be sharing the fixes.Cendyne

If you read Cendyne’s post, you may have nodded along with that remark and not appreciate the degree to which our naga friend was putting it mildly. So I thought I’d share some of my knowledge about real-world database cryptography in an accessible and fun format in the hopes that it might serve as an introduction to the specialization.

Note: I’m also not going to fix Cendyne’s sketch of AnonCo’s software here–partly because I don’t want to get in the habit of assigning homework or required reading, but mostly because it’s kind of obvious once you’ve learned the basics.

If you don’t like furries, please feel free to leave this blog and read about this topic elsewhere.

Thanks to CMYKat for the awesome stickers.

Contents

- Database Cryptography?

- Cryptography for Relational Databases

- Cryptography for NoSQL Databases

- Searchable Encryption

- Order-{Preserving, Revealing} Encryption

- Deterministic Encryption

- Homomorphic Encryption

- Searchable Symmetric Encryption (SSE)

- You Can Have Little a HMAC, As a Treat

- Intermission

- Case Study: MongoDB Client-Side Encryption

- Wrapping Up

Database Cryptography?

The premise of database cryptography is deceptively simple: You have a database, of some sort, and you want to store sensitive data in said database.

The consequences of this simple premise are anything but simple. Let me explain.

The sensitive data you want to store may need to remain confidential, or you may need to provide some sort of integrity guarantees throughout your entire system, or sometimes both. Sometimes all of your data is sensitive, sometimes only some of it is. Sometimes the confidentiality requirements of your data extends to where within a dataset the record you want actually lives. Sometimes that’s true of some data, but not others, so your cryptography has to be flexible to support multiple types of workloads.

Other times, you just want your disks encrypted at rest so if they grow legs and walk out of the data center, the data cannot be comprehended by an attacker. And you can’t be bothered to work on this problem any deeper. This is usually what compliance requirements cover. Boxes get checked, executives feel safer about their operation, and the whole time nobody has really analyzed the risks they’re facing.

But we’re not settling for mere compliance on this blog. Furries have standards, after all.

So the first thing you need to do before diving into database cryptography is threat modelling. The first step in any good threat model is taking inventory; especially of assumptions, requirements, and desired outcomes. A few good starter questions:

- What database software is being used? Is it up to date?

- What data is being stored in which database software?

- How are databases oriented in the network of the overall system?

- Is your database properly firewalled from the public Internet?

- How does data flow throughout the network, and when do these data flows intersect with the database?

- Which applications talk to the database? What languages are they written in? Which APIs do they use?

- How will cryptography secrets be managed?

- Is there one key for everyone, one key per tenant, etc.?

- How are keys rotated?

- Do you use envelope encryption with an HSM, or vend the raw materials to your end devices?

The first two questions are paramount for deciding how to write software for database cryptography, before you even get to thinking about the cryptography itself.

(This is not a comprehensive set of questions to ask, either. A formal threat model is much deeper in the weeds.)

The kind of cryptography protocol you need for, say, storing encrypted CSV files an S3 bucket is vastly different from relational (SQL) databases, which in turn will be significantly different from schema-free (NoSQL) databases.

Furthermore, when you get to the point that you can start to think about the cryptography, you’ll often need to tackle confidentiality and integrity separately.

If that’s unclear, think of a scenario like, “I need to encrypt PII, but I also need to digitally sign the lab results so I know it wasn’t tampered with at rest.”

My point is, right off the bat, we’ve got a three-dimensional matrix of complexity to contend with:

- On one axis, we have the type of database.

- Flat-file

- Relational

- Schema-free

- On another, we have the basic confidentiality requirements of the data.

- Field encryption

- Row encryption

- Column encryption

- Unstructured record encryption

- Encrypting entire collections of records

- Finally, we have the integrity requirements of the data.

- Field authentication

- Row/column authentication

- Unstructured record authentication

- Collection authentication (based on e.g. Sparse Merkle Trees)

And then you have a fourth dimension that often falls out of operational requirements for databases: Searchability.

Why store data in a database if you have no way to index or search the data for fast retrieval?

If you’re starting to feel overwhelmed, you’re not alone. A lot of developers drastically underestimate the difficulty of the undertaking, until they run head-first into the complexity.

Some just phone it in with AES_Encrypt() calls in their MySQL queries. (Too bad ECB mode doesn’t provide semantic security!)

Which brings us to the meat of this blog post: The actual cryptography part.

Cryptography is the art of transforming information security problems into key management problems.Former coworker

Note: In the interest of time, I’m skipping over flat files and focusing instead on actual database technologies.

Cryptography for Relational Databases

Encrypting data in an SQL database seems simple enough, even if you’ve managed to shake off the complexity I teased from the introduction.

You’ve got data, you’ve got a column on a table. Just encrypt the data and shove it in a cell on that column and call it a day, right?

But, alas, this is a trap. There are so many gotchas that I can’t weave a coherent, easy-to-follow narrative between them all.

So let’s start with a simple question: where and how are you performing your encryption?

The Perils of Built-in Encryption Functions

MySQL provides functions called AES_Encrypt and AES_Decrypt, which many developers have unfortunately decided to rely on in the past.

It’s unfortunate because these functions implement ECB mode. To illustrate why ECB mode is bad, I encrypted one of my art commissions with AES in ECB mode:

The problems with ECB mode aren’t exactly “you can see the image through it,” because ECB-encrypting a compressed image won’t have redundancy (and thus can make you feel safer than you are).

ECB art is a good visual for the actual issue you should care about, however: A lack of semantic security.

A cryptosystem is considered semantically secure if observing the ciphertext doesn’t reveal information about the plaintext (except, perhaps, the length; which all cryptosystems leak to some extent). More information here.

ECB art isn’t to be confused with ECB poetry, which looks like this:

Oh little one, you’re growing up

You’ll soon be writing C

You’ll treat your ints as pointers

You’ll nest the ternary

You’ll cut and paste from github

And try cryptography

But even in your darkest hour

Do not use ECBCBC’s BEASTly when padding’s abused

And CTR’s fine til a nonce is reused

Some say it’s a CRIME to compress then encrypt

Or store keys in the browser (or use javascript)

Diffie Hellman will collapse if hackers choose your g

And RSA is full of traps when e is set to 3

Whiten! Blind! In constant time! Don’t write an RNG!

But failing all, and listen well: Do not use ECBThey’ll say “It’s like a one-time-pad!

The data’s short, it’s not so bad

the keys are long–they’re iron clad

I have a PhD!”

And then you’re front page Hacker News

Your passwords cracked–Adobe Blues.

Don’t leave your penguins showing through,

Do not use ECB— Ben Nagy, PoC||GTFO 0x04:13

Most people reading this probably know better than to use ECB mode already, and don’t need any of these reminders, but there is still a lot of code that inadvertently uses ECB mode to encrypt data in the database.

Also, SHOW processlist; leaks your encryption keys. Oops.

Application-layer Relational Database Cryptography

Whether burned by ECB or just cautious about not giving your secrets to the system that stores all the ciphertext protected by said secret, a common next step for developers is to simply encrypt in their server-side application code.

And, yes, that’s part of the answer. But how you encrypt is important.

“I’ll encrypt with CBC mode.”

If you don’t authenticate your ciphertext, you’ll be sorry. Maybe try again?

“Okay, fine, I’ll use an authenticated mode like GCM.”

Did you remember to make the table and column name part of your AAD? What about the primary key of the record?

“What on Earth are you talking about, Soatok?”

Welcome to the first footgun of database cryptography!

Confused Deputies

Encrypting your sensitive data is necessary, but not sufficient. You need to also bind your ciphertexts to the specific context in which they are stored.

To understand why, let’s take a step back: What specific threat does encrypting your database records protect against?

We’ve already established that “your disks walk out of the datacenter” is a “full disk encryption” problem, so if you’re using application-layer cryptography to encrypt data in a relational database, your threat model probably involves unauthorized access to the database server.

What, then, stops an attacker from copying ciphertexts around?

Let’s say I have a legitimate user account with an ID 12345, and I want to read your street address, but it’s encrypted in the database. But because I’m a clever hacker, I have unfettered access to your relational database server.

All I would need to do is simply…

UPDATE table SET addr_encrypted = 'your-ciphertext' WHERE id = 12345

…and then access the application through my legitimate access. Bam, data leaked. As an attacker, I can probably even copy fields from other columns and it will just decrypt. Even if you’re using an authenticated mode.

We call this a confused deputy attack, because the deputy (the component of the system that has been delegated some authority or privilege) has become confused by the attacker, and thus undermined an intended security goal.

The fix is to use the AAD parameter from the authenticated mode to bind the data to a given context. (AAD = Additional Authenticated Data.)

- $addr = aes_gcm_encrypt($addr, $key);+ $addr = aes_gcm_encrypt($addr, $key, canonicalize([+ $tableName,+ $columnName,+ $primaryKey+ ]);

Now if I start cutting and pasting ciphertexts around, I get a decryption failure instead of silently decrypting plaintext.

This may sound like a specific vulnerability, but it’s more of a failure to understand an important general lesson with database cryptography:

Where your data lives is part of its identity, and MUST be authenticated.Soatok’s Rule of Database Cryptography

Canonicalization Attacks

In the previous section, I introduced a pseudocode called canonicalize(). This isn’t a pasto from some reference code; it’s an important design detail that I will elaborate on now.

First, consider you didn’t do anything to canonicalize your data, and you just joined strings together and called it a day…

function dumbCanonicalize( string $tableName, string $columnName, string|int $primaryKey): string { return $tableName . '_' . $columnName . '#' . $primaryKey;}

Consider these two inputs to this function:

dumbCanonicalize('customers', 'last_order_uuid', 123);dumbCanonicalize('customers_last_order', 'uuid', 123);

In this case, your AAD would be the same, and therefore, your deputy can still be confused (albeit in a narrower use case).

In Cendyne’s article, AnonCo did something more subtle: The canonicalization bug created a collision on the inputs to HKDF, which resulted in an unintentional key reuse.

Up until this point, their mistake isn’t relevant to us, because we haven’t even explored key management at all. But the same design flaw can re-emerge in multiple locations, with drastically different consequence.

Multi-Tenancy

Once you’ve implemented a mitigation against Confused Deputies, you may think your job is done. And it very well could be.

Often times, however, software developers are tasked with building support for Bring Your Own Key (BYOK).

This is often spawned from a specific compliance requirement (such as cryptographic shredding; i.e. if you erase the key, you can no longer recover the plaintext, so it may as well be deleted).

Other times, this is driven by a need to cut costs: Storing different users’ data in the same database server, but encrypting it such that they can only encrypt their own records.

Two things can happen when you introduce multi-tenancy into your database cryptography designs:

- Invisible Salamanders becomes a risk, due to multiple keys being possible for any given encrypted record.

- Failure to address the risk of Invisible Salamanders can undermine your protection against Confused Deputies, thereby returning you to a state before you properly used the AAD.

So now you have to revisit your designs and ensure you’re using a key-committing authenticated mode, rather than just a regular authenticated mode.

Isn’t cryptography fun?

“What Are Invisible Salamanders?”

This refers to a fun property of AEAD modes based on Polynomical MACs. Basically, if you:

- Encrypt one message under a specific key and nonce.

- Encrypt another message under a separate key and nonce.

…Then you can get the same exact ciphertext and authentication tag. Performing this attack requires you to control the keys for both encryption operations.

This was first demonstrated in an attack against encrypted messaging applications, where a picture of a salamander was hidden from the abuse reporting feature because another attached file had the same authentication tag and ciphertext, and you could trick the system if you disclosed the second key instead of the first. Thus, the salamander is invisible to attackers.

We’re not quite done with relational databases yet, but we should talk about NoSQL databases for a bit. The final topic in scope applies equally to both, after all.

Cryptography for NoSQL Databases

Most of the topics from relational databases also apply to NoSQL databases, so I shall refrain from duplicating them here. This article is already sufficiently long to read, after all, and I dislike redundancy.

NoSQL is Built Different

The main thing that NoSQL databases offer in the service of making cryptographers lose sleep at night is the schema-free nature of NoSQL designs.

What this means is that, if you’re using a client-side encryption library for a NoSQL database, the previous concerns about confused deputy attacks are amplified by the malleability of the document structure.

Additionally, the previously discussed cryptographic attacks against the encryption mode may be less expensive for an attacker to pull off.

Consider the following record structure, which stores a bunch of data stored with AES in CBC mode:

{ "encrypted-data-key": "<blob>", "name": "<ciphertext>", "address": [ "<ciphertext>", "<ciphertext>" ], "social-security": "<ciphertext>", "zip-code": "<ciphertext>"}

If this record is decrypted with code that looks something like this:

$decrypted = [];// ... snip ...foreach ($record['address'] as $i => $addrLine) { try { $decrypted['address'][$i] = $this->decrypt($addrLine); } catch (Throwable $ex) { // You'd never deliberately do this, but it's for illustration $this->doSomethingAnOracleCanObserve($i); // This is more believable, of course: $this->logDecryptionError($ex, $addrLine); $decrypted['address'][$i] = ''; }}

Then you can keep appending rows to the "address" field to reduce the number of writes needed to exploit a padding oracle attack against any of the <ciphertext> fields.

This isn’t to say that NoSQL is less secure than SQL, from the context of client-side encryption. However, the powerful feature sets that NoSQL users are accustomed to may also give attackers a more versatile toolkit to work with.

Record Authentication

A pedant may point out that record authentication applies to both SQL and NoSQL. However, I mostly only observe this feature in NoSQL databases and document storage systems in the wild, so I’m shoving it in here.

Encrypting fields is nice and all, but sometimes what you want to know is that your unencrypted data hasn’t been tampered with as it flows through your system.

The trivial way this is done is by using a digital signature algorithm over the whole record, and then appending the signature to the end. When you go to verify the record, all of the information you need is right there.

This works well enough for most use cases, and everyone can pack up and go home. Nothing more to see here.

Except…

When you’re working with NoSQL databases, you often want systems to be able to write to additional fields, and since you’re working with schema-free blobs of data rather than a normalized set of relatable tables, the most sensible thing to do is to is to append this data to the same record.

Except, oops! You can’t do that if you’re shoving a digital signature over the record. So now you need to specify which fields are to be included in the signature.

And you need to think about how to model that in a way that doesn’t prohibit schema upgrades nor allow attackers to perform downgrade attacks. (See below.)

Art: CMYKat

Furthermore, as with preventing confused deputy and/or canonicalization attacks above, you must also include the fully qualified path of each field in the data that gets signed.

As I said with encryption before, but also true here:

Where your data lives is part of its identity, and MUST be authenticated.Soatok’s Rule of Database Cryptography

This requirement holds true whether you’re using symmetric-key authentication (i.e. HMAC) or asymmetric-key digital signatures (e.g. EdDSA).

Bonus: A Maximally Schema-Free, Upgradeable Authentication Design

Okay, how do you solve this problem so that you can perform updates and upgrades to your schema but without enabling attackers to downgrade the security? Here’s one possible design.

Let’s say you have two metadata fields on each record:

- A compressed binary string representing which fields should be authenticated. This field is, itself, not authenticated. Let’s call this

meta-auth. - A compressed binary string representing which of the authenticated fields should also be encrypted. This field is also authenticated. This is at most the same length as the first metadata field. Let’s call this

meta-enc.

Furthermore, you will specify a canonical field ordering for both how data is fed into the signature algorithm as well as the field mappings in meta-auth and meta-enc.

{ "example": { "credit-card": { "number": /* encrypted */, "expiration": /* encrypted */, "ccv": /* encrypted */ }, "superfluous": { "rewards-member": null } }, "meta-auth": compress_bools([ true, /* example.credit-card.number */ true, /* example.credit-card.expiration */ true, /* example.credit-card.ccv */ false, /* example.superfluous.rewards-member */ true /* meta-enc */ ]), "meta-enc": compress_bools([ true, /* example.credit-card.number */ true, /* example.credit-card.expiration */ true, /* example.credit-card.ccv */ false /* example.superfluous.rewards-member */ ]), "signature": /* -- snip -- */}

When you go to append data to an existing record, you’ll need to update meta-auth to include the mapping of fields based on this canonical ordering to ensure only the intended fields get validated.

When you update your code to add an additional field that is intended to be signed, you can roll that out for new records and the record will continue to be self-describing:

- New records will have the additional field flagged as authenticated in

meta-auth(andmeta-encwill grow) - Old records will not, but your code will still sign them successfully

- To prevent downgrade attacks, simply include a schema version ID as an additional plaintext field that gets authenticated. An attacker who tries to downgrade will need to be able to produce a valid signature too.

You might think meta-auth gives an attacker some advantage, but this only includes which fields are included in the security boundary of the signature or MAC, which allows unauthenticated data to be appended for whatever operational purpose without having to update signatures or expose signing keys to a wider part of the network.

{ "example": { "credit-card": { "number": /* encrypted */, "expiration": /* encrypted */, "ccv": /* encrypted */ }, "superfluous": { "rewards-member": null } }, "meta-auth": compress_bools([ true, /* example.credit-card.number */ true, /* example.credit-card.expiration */ true, /* example.credit-card.ccv */ false, /* example.superfluous.rewards-member */ true, /* meta-enc */ true /* meta-version */ ]), "meta-enc": compress_bools([ true, /* example.credit-card.number */ true, /* example.credit-card.expiration */ true, /* example.credit-card.ccv */ false, /* example.superfluous.rewards-member */ true /* meta-version */ ]), "meta-version": 0x01000000, "signature": /* -- snip -- */}

If an attacker tries to use the meta-auth field to mess with a record, the best they can hope for is an Invalid Signature exception (assuming the signature algorithm is secure to begin with).

Even if they keep all of the fields the same, but play around with the structure of the record (e.g. changing the XPath or equivalent), so long as the path is authenticated with each field, breaking this is computationally infeasible.

Searchable Encryption

If you’ve managed to make it through the previous sections, congratulations, you now know enough to build a secure but completely useless database.

Okay, put away the pitchforks; I will explain.

Part of the reason why we store data in a database, rather than a flat file, is because we want to do more than just read and write. Sometimes computer scientists want to compute. Almost always, you want to be able to query your database for a subset of records based on your specific business logic needs.

And so, a database which doesn’t do anything more than store ciphertext and maybe signatures is pretty useless to most people. You’d have better luck selling Monkey JPEGs to furries than convincing most businesses to part with their precious database-driven report generators.

So whenever one of your users wants to actually use their data, rather than just store it, they’re forced to decide between two mutually exclusive options:

- Encrypting the data, to protect it from unauthorized disclosure, but render it useless

- Doing anything useful with the data, but leaving it unencrypted in the database

This is especially annoying for business types that are all in on the Zero Trust buzzword.

Fortunately, the cryptographers are at it again, and boy howdy do they have a lot of solutions for this problem.

Order-{Preserving, Revealing} Encryption

On the fun side of things, you have things like Order-Preserving and Order-Revealing Encryption, which Matthew Green wrote about at length.

[D]atabase encryption has been a controversial subject in our field. I wish I could say that there’s been an actual debate, but it’s more that different researchers have fallen into different camps, and nobody has really had the data to make their position in a compelling way. There have actually been some very personal arguments made about it.Attack of the week: searchable encryption and the ever-expanding leakage function

The problem with these designs is that they have a significant enough leakage that it no longer provides semantic security.

Colors inverted to fit my blog’s theme better.

To put it in other words: These designs are only marginally better than ECB mode, and probably deserve their own poems too.

Order revealing

Reveals much more than order

Softcore ECBOrder preserving

Semantic security?

Only in your dreamsHaiku for your consideration

Deterministic Encryption

Here’s a simpler, but also terrible, idea for searchable encryption: Simply give up on semantic security entirely.

If you recall the AES_{De,En}crypt() functions built into MySQL I mentioned at the start of this article, those are the most common form of deterministic encryption I’ve seen in use.

SELECT * FROM foo WHERE bar = AES_Encrypt('query', 'key');

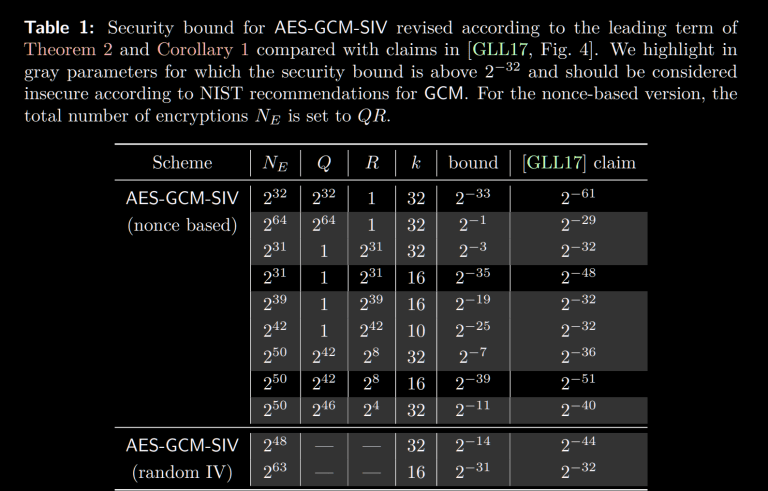

However, there are slightly less bad variants. If you use AES-GCM-SIV with a static nonce, your ciphertexts are fully deterministic, and you can encrypt a small number of distinct records safely before you’re no longer secure.

That’s certainly better than nothing, but you also can’t mitigate confused deputy attacks. But we can do better than this.

Homomorphic Encryption

In a safer plane of academia, you’ll find homomorphic encryption, which researchers recently demonstrated with serving Wikipedia pages in a reasonable amount of time.

Homomorphic encryption allows computations over the ciphertext, which will be reflected in the plaintext, without ever revealing the key to the entity performing the computation.

If this sounds vaguely similar to the conditions that enable chosen-ciphertext attacks, you probably have a good intuition for how it works: RSA is homomorphic to multiplication, AES-CTR is homomorphic to XOR. Fully homomorphic encryption uses lattices, which enables multiple operations but carries a relatively enormous performance cost.

Homomorphic encryption sometimes intersects with machine learning, because the notion of training an encrypted model by feeding it encrypted data, then decrypting it after-the-fact is desirable for certain business verticals. Your data scientists never see your data, and you have some plausible deniability about the final ML model this work produces. This is like a Siren song for Venture Capitalist-backed medical technology companies. Tech journalists love writing about it.

However, a less-explored use case is the ability to encrypt your programs but still get the correct behavior and outputs. Although this sounds like a DRM technology, it’s actually something that individuals could one day use to prevent their ISPs or cloud providers from knowing what software is being executed on the customer’s leased hardware. The potential for a privacy win here is certainly worth pondering, even if you’re a tried and true Pirate Party member.

Art: CMYKat

Searchable Symmetric Encryption (SSE)

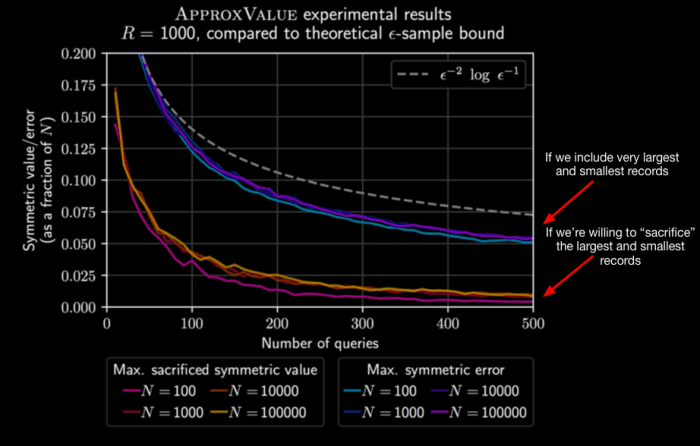

Forget about working at the level of fields and rows or individual records. What if we, instead, worked over collections of documents, where each document is viewed as a set of keywords from a keyword space?

That’s the basic premise of SSE: Encrypting collections of documents rather than individual records.

The actual implementation details differ greatly between designs. They also differ greatly in their leakage profiles and susceptibility to side-channel attacks.

Some schemes use a so-called trapdoor permutation, such as RSA, as one of their building blocks.

Some schemes only allow for searching a static set of records, while others can accommodate new data over time (with the trade-off between more leakage or worse performance).

If you’re curious, you can learn more about SSE here, and see some open source SEE implementations online here.

You’re probably wondering, “If SSE is this well-studied and there are open source implementations available, why isn’t it more widely used?”

Your guess is as good as mine, but I can think of a few reasons:

- The protocols can be a little complicated to implement, and aren’t shipped by default in cryptography libraries (i.e. OpenSSL’s libcrypto or libsodium).

- Every known security risk in SSE is the product of a trade-offs, rather than there being a single winner for all use cases that developers can feel comfortable picking.

- Insufficient marketing and developer advocacy.

SSE schemes are mostly of interest to academics, although Seny Kamara (Brown Univeristy professior and one of the luminaries of searchable encryption) did try to develop an app called Pixek which used SSE to encrypt photos.

Maybe there’s room for a cryptography competition on searchable encryption schemes in the future.

You Can Have Little a HMAC, As a Treat

Finally, I can’t talk about searchable encryption without discussing a technique that’s older than dirt by Internet standards, that has been independently reinvented by countless software developers tasked with encrypting database records.

The oldest version I’ve been able to track down dates to 2006 by Raul Garcia at Microsoft, but I’m not confident that it didn’t exist before.

The idea I’m alluding to goes like this:

- Encrypt your data, securely, using symmetric cryptography.

(Hopefully your encryption addresses the considerations outlined in the relevant sections above.) - Separately, calculate an HMAC over the unencrypted data with a separate key used exclusively for indexing.

When you need to query your data, you can just recalculate the HMAC of your challenge and fetch the records that match it. Easy, right?

Even if you rotate your keys for encryption, you keep your indexing keys static across your entire data set. This lets you have durable indexes for encrypted data, which gives you the ability to do literal lookups for the performance hit of a hash function.

Additionally, everyone has HMAC in their toolkit, so you don’t have to move around implementations of complex cryptographic building blocks. You can live off the land. What’s not to love?

However, if you stopped here, we regret to inform you that your data is no longer indistinguishable from random, which probably undermines the security proof for your encryption scheme.

Of course, you don’t have to stop with the addition of plain HMAC to your database encryption software.

Take a page from Troy Hunt: Truncate the output to provide k-anonymity rather than a direct literal look-up.

“K-What Now?”

Imagine you have a full HMAC-SHA256 of the plaintext next to every ciphertext record with a static key, for searchability.

Each HMAC output corresponds 1:1 with a unique plaintext.

Because you’re using HMAC with a secret key, an attacker can’t just build a rainbow table like they would when attempting password cracking, but it still leaks duplicate plaintexts.

For example, an HMAC-SHA256 output might look like this: 04a74e4c0158e34a566785d1a5e1167c4e3455c42aea173104e48ca810a8b1ae

If you were to slice off most of those bytes (e.g. leaving only the last 3, which in the previous example yields a8b1ae), then with sufficient records, multiple plaintexts will now map to the same truncated HMAC tag.

Which means if you’re only revealing a truncated HMAC tag to the database server (both when storing records or retrieving them), you can now expect false positives due to collisions in your truncated HMAC tag.

These false positives give your data a discrete set of anonymity (called k-anonymity), which means an attacker with access to your database cannot:

- Distinguish between two encrypted records with the same short HMAC tag.

- Reverse engineer the short HMAC tag into a single possible plaintext value, even if they can supply candidate queries and study the tags sent to the database.

As with SSE above, this short HMAC technique exposes a trade-off to users.

- Too much k-anonymity (i.e. too many false positives), and you will have to decrypt-then-discard multiple mismatching records. This can make queries slow.

- Not enough k-anonymity (i.e. insufficient false positives), and you’re no better off than a full HMAC.

Even more troublesome, the right amount to truncate is expressed in bits (not bytes), and calculating this value depends on the number of unique plaintext values you anticipate in your dataset. (Fortunately, it grows logarithmically, so you’ll rarely if ever have to tune this.)

If you’d like to play with this idea, here’s a quick and dirty demo script.

Intermission

If you started reading this post with any doubts about Cendyne’s statement that “Database cryptography is hard”, by making it to this point, they’ve probably been long since put to rest.

Conversely, anyone that specializes in this topic is probably waiting for me to say anything novel or interesting; their patience wearing thin as I continue to rehash a surface-level introduction of their field without really diving deep into anything.

Thus, if you’ve read this far, I’d like to demonstrate the application of what I’ve covered thus far into a real-world case study into an database cryptography product.

Case Study: MongoDB Client-Side Encryption

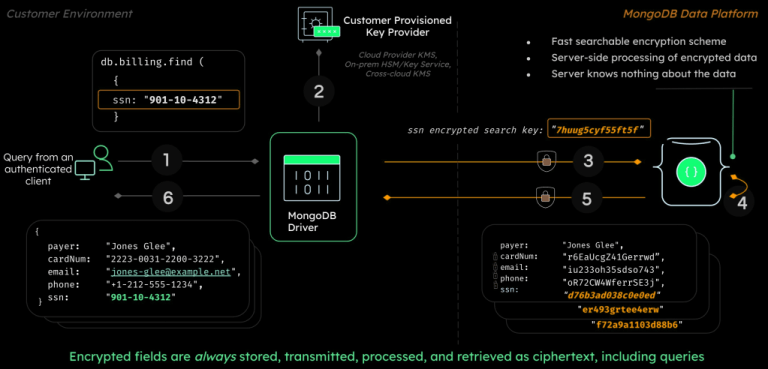

MongoDB is an open source schema-free NoSQL database. Last year, MongoDB made waves when they announced Queryable Encryption in their upcoming client-side encryption release.

A statement at the bottom of their press release indicates that this isn’t clown-shoes:

Queryable Encryption was designed by MongoDB’s Advanced Cryptography Research Group, headed by Seny Kamara and Tarik Moataz, who are pioneers in the field of encrypted search. The Group conducts cutting-edge peer-reviewed research in cryptography and works with MongoDB engineering teams to transfer and deploy the latest innovations in cryptography and privacy to the MongoDB data platform.

If you recall, I mentioned Seny Kamara in the SSE section of this post. They certainly aren’t wrong about Kamara and Moataz being pioneers in this field.

So with that in mind, let’s explore the implementation in libmongocrypt and see how it stands up to scrutiny.

MongoCrypt: The Good

MongoDB’s encryption library takes key management seriously: They provide a KMS integration for cloud users by default (supporting both AWS and Azure).

MongoDB uses Encrypt-then-MAC with AES-CBC and HMAC-SHA256, which is congruent to what Signal does for message encryption.

How Is Queryable Encryption Implemented?

From the current source code, we can see that MongoCrypt generates several different types of tokens, using HMAC (calculation defined here).

According to their press release:

The feature supports equality searches, with additional query types such as range, prefix, suffix, and substring planned for future releases.

Which means that most of the juicy details probably aren’t public yet.

These HMAC-derived tokens are stored wholesale in the data structure, but most are encrypted before storage using AES-CTR.

There are more layers of encryption (using AEAD), server-side token processing, and more AES-CTR-encrypted edge tokens. All of this is finally serialized (implementation) as one blob for storage.

Since only the equality operation is currently supported (which is the same feature you’d get from HMAC), it’s difficult to speculate what the full feature set looks like.

However, since Kamara and Moataz are leading its development, it’s likely that this feature set will be excellent.

MongoCrypt: The Bad

Every call to do_encrypt() includes at most the Key ID (but typically NULL) as the AAD. This means that the concerns over Confused Deputies (and NoSQL specifically) are relevant to MongoDB.

However, even if they did support authenticating the fully qualified path to a field in the AAD for their encryption, their AEAD construction is vulnerable to the kind of canonicalization attack I wrote about previously.

First, observe this code which assembles the multi-part inputs into HMAC.

/* Construct the input to the HMAC */uint32_t num_intermediates = 0;_mongocrypt_buffer_t intermediates[3];// -- snip --if (!_mongocrypt_buffer_concat ( &to_hmac, intermediates, num_intermediates)) { CLIENT_ERR ("failed to allocate buffer"); goto done;}if (hmac == HMAC_SHA_512_256) { uint8_t storage[64]; _mongocrypt_buffer_t tag = {.data = storage, .len = sizeof (storage)}; if (!_crypto_hmac_sha_512 (crypto, Km, &to_hmac, &tag, status)) { goto done; } // Truncate sha512 to first 256 bits. memcpy (out->data, tag.data, MONGOCRYPT_HMAC_LEN);} else { BSON_ASSERT (hmac == HMAC_SHA_256); if (!_mongocrypt_hmac_sha_256 (crypto, Km, &to_hmac, out, status)) { goto done; }}

The implementation of _mongocrypt_buffer_concat() can be found here.

If either the implementation of that function, or the code I snipped from my excerpt, had contained code that prefixed every segment of the AAD with the length of the segment (represented as a uint64_t to make overflow infeasible), then their AEAD mode would not be vulnerable to canonicalization issues.

Using TupleHash would also have prevented this issue.

Silver lining for MongoDB developers: Because the AAD is either a key ID or NULL, this isn’t exploitable in practice.

The first cryptographic flaw sort of cancels the second out.

If the libmongocrypt developers ever want to mitigate Confused Deputy attacks, they’ll need to address this canonicalization issue too.

MongoCrypt: The Ugly

MongoCrypt supports deterministic encryption.

If you specify deterministic encryption for a field, your application passes a deterministic initialization vector to AEAD.

We already discussed why this is bad above.

Wrapping Up

This was not a comprehensive treatment of the field of database cryptography. There are many areas of this field that I did not cover, nor do I feel qualified to discuss.

However, I hope anyone who takes the time to read this finds themselves more familiar with the subject.

Additionally, I hope any developers who think “encrypting data in a database is [easy, trivial] (select appropriate)” will find this broad introduction a humbling experience.

https://soatok.blog/2023/03/01/database-cryptography-fur-the-rest-of-us/

#appliedCryptography #blockCipherModes #cryptography #databaseCryptography #databases #encryptedSearch #HMAC #MongoCrypt #MongoDB #QueryableEncryption #realWorldCryptography #security #SecurityGuidance #SQL #SSE #symmetricCryptography #symmetricSearchableEncryption

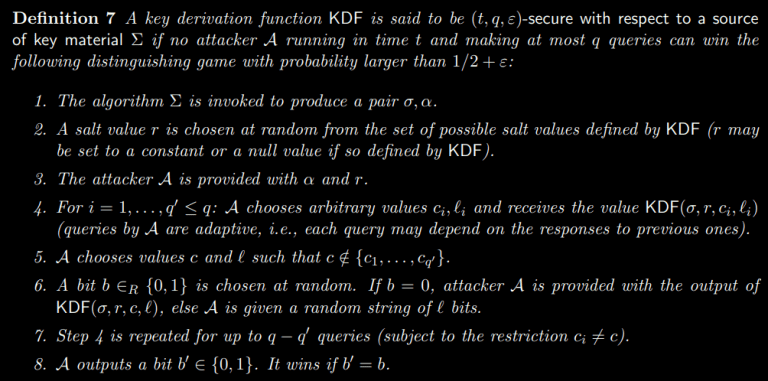

NIST opened public comments on SP 800-108 Rev. 1 (the NIST recommendations for Key Derivation Functions) last month. The main thing that’s changed from the original document published in 2009 is the inclusion of the Keccak-based KMAC alongside the incumbent algorithms.One of the recommendations of SP 800-108 is called “KDF in Counter Mode”. A related document, SP 800-56C, suggests using a specific algorithm called HKDF instead of the generic Counter Mode construction from SP 800-108–even though they both accomplish the same goal.

Isn’t standards compliance fun?

Interestingly, HKDF isn’t just an inconsistently NIST-recommended KDF, it’s also a common building block in a software developer’s toolkit which sees a lot of use in different protocols.

Unfortunately, the way HKDF is widely used is actually incorrect given its formal security definition. I’ll explain what I mean in a moment.

Art: Scruff

What is HKDF?

To first understand what HKDF is, you first need to know about HMAC.HMAC is a standard message authentication code (MAC) algorithm built with cryptographic hash functions (that’s the H). HMAC is specified in RFC 2104 (yes, it’s that old).

HKDF is a key-derivation function that uses HMAC under-the-hood. HKDF is commonly used in encryption tools (Signal, age). HKDF is specified in RFC 5869.

HKDF is used to derive a uniformly-random secret key, typically for use with symmetric cryptography algorithms. In any situation where a key might need to be derived, you might see HKDF being used. (Although, there may be better algorithms.)

Art: LvJ

How Developers Understand and Use HKDF

If you’re a software developer working with cryptography, you’ve probably seen an API in the crypto module for your programming language that looks like this, or maybe this.hash_hkdf( string $algo, string $key, int $length = 0, string $info = "", string $salt = ""): string

Software developers that work with cryptography will typically think of the HKDF parameters like so:

$algo— which hash function to use$key— the input key, from which multiple keys can be derived$length— how many bytes to derive$info— some arbitrary string used to bind a derived key to an intended context$salt— some additional randomness (optional)The most common use-case of HKDF is to implement key-splitting, where a single input key (the Initial Keying Material, or IKM) is used to derive two or more independent keys, so that you’re never using a single key for multiple algorithms.

See also:

[url=https://github.com/defuse/php-encryption]defuse/php-encryption[/url], a popular PHP encryption library that does exactly what I just described.At a super high level, the HKDF usage I’m describing looks like this:

class MyEncryptor {protected function splitKeys(CryptographyKey $key, string $salt): array { $encryptKey = new CryptographyKey(hash_hkdf( 'sha256', $key->getRawBytes(), 32, 'encryption', $salt )); $authKey = new CryptographyKey(hash_hkdf( 'sha256', $key->getRawBytes(), 32, 'message authentication', $salt )); return [$encryptKey, $authKey];}public function encryptString(string $plaintext, CryptographyKey $key): string{ $salt = random_bytes(32); [$encryptKey, $hmacKey] = $this->splitKeys($key, $salt); // ... encryption logic here ... return base64_encode($salt . $ciphertext . $mac);}public function decryptString(string $encrypted, CryptographyKey $key): string{ $decoded = base64_decode($encrypted); $salt = mb_substr($decoded, 0, 32, '8bit'); [$encryptKey, $hmacKey] = $this->splitKeys($key, $salt); // ... decryption logic here ... return $plaintext;}// ... other method here ...}

Unfortunately, anyone who ever does something like this just violated one of the core assumptions of the HKDF security definition and no longer gets to claim “KDF security” for their construction. Instead, your protocol merely gets to claim “PRF security”.

Art: Harubaki

KDF? PRF? OMGWTFBBQ?

Let’s take a step back and look at some basic concepts.(If you want a more formal treatment, read this Stack Exchange answer.)

PRF: Pseudo-Random Functions

A pseudorandom function (PRF) is an efficient function that emulates a random oracle.“What the hell’s a random oracle?” you ask? Well, Thomas Pornin has the best explanation for random oracles:

A random oracle is described by the following model:

- There is a black box. In the box lives a gnome, with a big book and some dice.

- We can input some data into the box (an arbitrary sequence of bits).

- Given some input that he did not see beforehand, the gnome uses his dice to generate a new output, uniformly and randomly, in some conventional space (the space of oracle outputs). The gnome also writes down the input and the newly generated output in his book.

- If given an already seen input, the gnome uses his book to recover the output he returned the last time, and returns it again.

So a random oracle is like a kind of hash function, such that we know nothing about the output we could get for a given input message m. This is a useful tool for security proofs because they allow to express the attack effort in terms of number of invocations to the oracle.

The problem with random oracles is that it turns out to be very difficult to build a really “random” oracle. First, there is no proof that a random oracle can really exist without using a gnome. Then, we can look at what we have as candidates: hash functions. A secure hash function is meant to be resilient to collisions, preimages and second preimages. These properties do not imply that the function is a random oracle.

Thomas Pornin

Alternatively, Wikipedia has a more formal definition available to the academic-inclined.In practical terms, we can generate a strong PRF out of secure cryptographic hash functions by using a keyed construction; i.e. HMAC.

Thus, as long as your HMAC key is a secret, the output of HMAC can be generally treated as a PRF for all practical purposes. Your main security consideration (besides key management) is the collision risk if you truncate its output.

Art: LvJ

KDF: Key Derivation Functions

A key derivation function (KDF) is exactly what it says on the label: a cryptographic algorithm that derives one or more cryptographic keys from a secret input (which may be another cryptography key, a group element from a Diffie-Hellman key exchange, or a human-memorable password).Note that passwords should be used with a Password-Based Key Derivation Function, such as scrypt or Argon2id, not HKDF.

Despite what you may read online, KDFs do not need to be built upon cryptographic hash functions, specifically; but in practice, they often are.

A notable counter-example to this hash function assumption: CMAC in Counter Mode (from NIST SP 800-108) uses AES-CMAC, which is a variable-length input variant of CBC-MAC. CBC-MAC uses a block cipher, not a hash function.

Regardless of the construction, KDFs use a PRF under the hood, and the output of a KDF is supposed to be a uniformly random bit string.

Art: LvJ

PRF vs KDF Security Definitions

The security definition for a KDF has more relaxed requirements than PRFs: PRFs require the secret key be uniformly random. KDFs do not have this requirement.If you use a KDF with a non-uniformly random IKM, you probably need the KDF security definition.

If your IKM is already uniformly random (i.e. the “key separation” use case), you can get by with just a PRF security definition.

After all, the entire point of KDFs is to allow a congruent security level as you’d get from uniformly random secret keys, without also requiring them.

However, if you’re building a protocol with a security requirement satisfied by a KDF, but you actually implemented a PRF (i.e., not a KDF), this is a security vulnerability in your cryptographic design.

Art: LvJ

The HKDF Algorithm

HKDF is an HMAC-based KDF. Its algorithm consists of two distinct steps:

HKDF-Extractuses the Initial Keying Material (IKM) and Salt to produce a Pseudo-Random Key (PRK).HKDF-Expandactually derives the keys using PRK, theinfoparameter, and a counter (from0to255) for each hash function output needed to generate the desired output length.If you’d like to see an implementation of this algorithm,

defuse/php-encryptionprovides one (since it didn’t land in PHP until 7.1.0). Alternatively, there’s a Python implementation on Wikipedia that uses HMAC-SHA256.This detail about the two steps will matter a lot in just a moment.

Art: Swizz

How HKDF Salts Are Misused

The HKDF paper, written by Hugo Krawczyk, contains the following definition (page 7).

The paper goes on to discuss the requirements for authenticating the salt over the communication channel, lest the attacker have the ability to influence it.

A subtle detail of this definition is that the security definition says that A salt value

, not Multiple salt values.

Which means: You’re not supposed to use HKDF with a constant IKM, info label, etc. but vary the salt for multiple invocations. The salt must either be a fixed random value, or NULL.

The HKDF RFC makes this distinction even less clear when it argues for random salts.

We stress, however, that the use of salt adds significantly to the strength of HKDF, ensuring independence between different uses of the hash function, supporting “source-independent” extraction, and strengthening the analytical results that back the HKDF design.Random salt differs fundamentally from the initial keying material in two ways: it is non-secret and can be re-used. As such, salt values are available to many applications. For example, a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG) that continuously produces outputs by applying HKDF to renewable pools of entropy (e.g., sampled system events) can fix a salt value and use it for multiple applications of HKDF without having to protect the secrecy of the salt. In a different application domain, a key agreement protocol deriving cryptographic keys from a Diffie-Hellman exchange can derive a salt value from public nonces exchanged and authenticated between communicating parties as part of the key agreement (this is the approach taken in [IKEv2]).

RFC 5869, section 3.1

Okay, sure. Random salts are better than a NULL salt. And while this section alludes to “[fixing] a salt value” to “use it for multiple applications of HKDF without having to protect the secrecy of the salt”, it never explicitly states this requirement. Thus, the poor implementor is left to figure this out on their own.Thus, because it’s not using HKDF in accordance with its security definition, many implementations (such as the PHP encryption library we’ve been studying) do not get to claim that their construction has KDF security.

Instead, they only get to claim “Strong PRF” security, which you can get from just using HMAC.

Art: LvJ

What Purpose Do HKDF Salts Actually Serve?

Recall that the HKDF algorithm uses salts in the HDKF-Extract step. Salts in this context were intended for deriving keys from a Diffie-Hellman output, or a human-memorable password.In the case of [Elliptic Curve] Diffie-Hellman outputs, the result of the key exchange algorithm is a random group element, but not necessarily uniformly random bit string. There’s some structure to the output of these functions. This is why you always, at minimum, apply a cryptographic hash function to the output of [EC]DH before using it as a symmetric key.

HKDF uses salts as a mechanism to improve the quality of randomness when working with group elements and passwords.

Extending the nonce for a symmetric-key AEAD mode is a good idea, but using HKDF’s salt parameter specifically to accomplish this is a misuse of its intended function, and produces a weaker argument for your protocol’s security than would otherwise be possible.

How Should You Introduce Randomness into HKDF?

Just shove it in theinfoparameter.

Art: LvJ

It may seem weird, and defy intuition, but the correct way to introduce randomness into HKDF as most developers interact with the algorithm is to skip the salt parameter entirely (either fixing it to a specific value for domain-separation or leaving it NULL), and instead concatenate data into the

infoparameter.class BetterEncryptor extends MyEncryptor {protected function splitKeys(CryptographyKey $key, string $salt): array { $encryptKey = new CryptographyKey(hash_hkdf( 'sha256', $key->getRawBytes(), 32, $salt . 'encryption', '' // intentionally empty )); $authKey = new CryptographyKey(hash_hkdf( 'sha256', $key->getRawBytes(), 32, $salt . 'message authentication', '' // intentionally empty )); return [$encryptKey, $authKey];}}

Of course, you still have to watch out for canonicalization attacks if you’re feeding multi-part messages into the info tag.

Another advantage: This also lets you optimize your HKDF calls by caching the PRK from the

HKDF-Extractstep and reuse it for multiple invocations ofHKDF-Expandwith a distinctinfo. This allows you to reduce the number of hash function invocations fromto

(since each HMAC involves two hash function invocations).

Notably, this HKDF salt usage was one of the things that was changed in V3/V4 of PASETO.

Does This Distinction Really Matter?

If it matters, your cryptographer will tell you it matters–which probably means they have a security proof that assumes the KDF security definition for a very good reason, and you’re not allowed to violate that assumption.Otherwise, probably not. Strong PRF security is still pretty damn good for most threat models.

Art: LvJ

Closing Thoughts

If your takeaway was, “Wow, I feel stupid,” don’t, because you’re in good company.I’ve encountered several designs in my professional life that shoved the randomness into the

infoparameter, and it perplexed me because there was a perfectly good salt parameter right there. It turned out, I was wrong to believe that, for all of the subtle and previously poorly documented reasons discussed above. But now we both know, and we’re all better off for it.So don’t feel dumb for not knowing. I didn’t either, until this was pointed out to me by a very patient colleague.

“Feeling like you were stupid” just means you learned.

(Art: LvJ)Also, someone should really get NIST to be consistent about whether you should use HKDF or “KDF in Counter Mode with HMAC” as a PRF, because SP 800-108’s new revision doesn’t concede this point at all (presumably a relic from the 2009 draft).

This concession was made separately in 2011 with SP 800-56C revision 1 (presumably in response to criticism from the 2010 HKDF paper), and the present inconsistency is somewhat vexing.

(On that note, does anyone actually use the NIST 800-108 KDFs instead of HKDF? If so, why? Please don’t say you need CMAC…)

Bonus Content

These questions were asked after this blog post initially went public, and I thought they were worth adding. If you ask a good question, it may end up being edited in at the end, too.

Art: LvJ

Why Does HKDF use the Salt as the HMAC key in the Extract Step? (via r/crypto)

Broadly speaking, when applying a PRF to two “keys”, you get to decide which one you treat as the “key” in the underlying API.HMAC’s API is HMACalg(key, message), but how HKDF uses it might as well be HMACalg(key1, key2).

The difference here seems almost arbitrary, but there’s a catch.

HKDF was designed for Diffie-Hellman outputs (before ECDH was the norm), which are generally able to be much larger than the block size of the underlying hash function. 2048-bit DH results fit in 256 bytes, which is 4 times the SHA256 block size.

If you have to make a decision, using the longer input (DH output) as the message is more intuitive for analysis than using it as the key, due to pre-hashing. I’ve discussed the counter-intuitive nature of HMAC’s pre-hashing behavior at length in this post, if you’re interested.

So with ECDH, it literally doesn’t matter which one was used (unless you have a weird mismatch in hash functions and ECC groups; i.e. NIST P-521 with SHA-224).

But before the era of ECDH, it was important to use the salt as the HMAC key in the extract step, since they were necessarily smaller than a DH group element.

Thus, HKDF chose HMACalg(salt, IKM) instead of HMACalg(IKM, salt) for the calculation of PRK in the HKDF-Extract step.

Neil Madden also adds that the reverse would create a chicken-egg situation, but I personally suspect that the pre-hashing would be more harmful to the security analysis than merely supplying a non-uniformly random bit string as an HMAC key in this specific context.

My reason for believing this is, when a salt isn’t supplied, it defaults to a string of

0x00bytes as long as the output size of the underlying hash function. If the uniform randomness of the salt mattered that much, this wouldn’t be a tolerable condition.https://soatok.blog/2021/11/17/understanding-hkdf/

#cryptographicHashFunction #cryptography #hashFunction #HMAC #KDF #keyDerivationFunction #securityDefinition #SecurityGuidance